Defination: Land is one factor amongst four factors of production. Land comprises all of natural resources that occur naturally, these included all geographical locations, mineral deposits, soil, geostationary orbits and it also includes some portion of electromagnetic spectrum. Depending on the title, land ownership give holder the rights to all natural resources on the land. These may include water, plants, human and animal life, fossils, soil, minerals, electromagnetic features, geographical location, and geophysical occurrences.

*Land does not include building or equipments that not occur naturally.

Explanation of Land:

Land is any place or space you will use to produce goods or services, it is one of primary factors of production without it you cannot produces anything, for instances if you are going to produce any cold drink, you need to setup machineries, hire labours and invest capital and use entrepreneurship, so if you think for producing cold drink the idea that take the first place in your mind would be that where you should setup your industry ? so for setting up an industry you need to own or borrow a land. thats why it is called primary factor of production because all other factors are aside and land is aside.

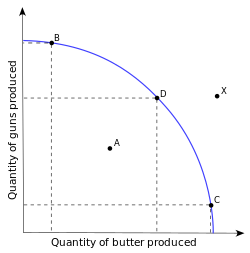

Following Pictures are an example of land.

of one index u, occurring at quantity

of one index u, occurring at quantity  of the goods bundle being evaluated, the corresponding value

of the goods bundle being evaluated, the corresponding value  of the other index v satisfies a relationship of the form

of the other index v satisfies a relationship of the form ,

,